Both of the Abu Simbel temples were moved to higher ground in 1963 - 1968, before the completion of the Aswan high dam which would have flooded them. The $40 million project is the greatest feat of rescue archaeology ever attempted. The Rameses temple was cut from the cliff, segmented into 1036 numbered blocks weighing a total of about 15,000 tons and reassembled in a concrete shell above the new waterline. The broken torso of the second Rameses was replaced at the feet of the statues. The entire complex now looks out over Lake Nasser and the large number of tourists who visit every year.

The Pharaoh's Temple

March 22nd, 1813.Having, as I supposed, seen all the antiquities of Abu Simbel, I was about to ascend the sandy side of the mountain by the same way I had descended; when having luckily turned more to the southward, I fell in with what is yet visible of four immense colossal statues cut out of the rock, at a distance of about two hundred yards from the temple; they stand in a deep recess, excavated in the mountain; but it is greatly to be regretted, that they are now almost entirely buried beneath the sands, which are blown down here in torrents.

The entire head, and part of the chest and arms of one of the statues are above the surface; of the one next to it scarcely any part is visible, the head being broken off, and the body covered with sand to above the shoulders; of the other two, the bonnets only appear. It is difficult to determine whether these statues are in a sitting or standing posture; their backs adhere to a portion of rock, which projects from the main body, and which may represent a part of a chair, or may be merely a column for support. They do not front the river, like the Queen's temple, but are turned with their faces due north, towards the more fertile climes of Egypt, so that the line on which they stand forms an angle with the course of the river.

The head which is above the surface has a most expressive, youthful countenance, approaching nearer to the Grecian model of beauty than that of any ancient Egyptian figure I have seen; indeed, were it not for a thin oblong beard, it might well pass for a head of Pallas. This statue wears the high bonnet usually called the corn-measure, the arms are covered with hieroglyphics, deeply cut in the sand-stone and well executed; the statue measures seven yards across the shoulders, and cannot, therefore, if in an upright posture, be less than from sixty-five to seventy feet in height: the ear is one yard and four inches in length.

On the wall of the rock, in the center of the four statues, is the figure of the hawk-headed Osiris (now believed to be Ra-Harakhti), surmounted by a globe; beneath which, I suspect, could the sand be cleared away, a vast temple would be discovered, to the entrance of which the above colossal figures probably serve as ornaments in the same manner as the six belonging to the neighboring temple of Isis. The leveled face of the rock behind the colossal figures is covered with hieroglyphic characters; over which is a row of upwards of twenty sitting figures, cut out of the rock like the others, but so much defaced, that I could not make out distinctly, from below, what they were meant for; they are about six feet in height.

Judging from the features of the colossal statue visible above the sand, I should pronounce these works to belong to the finest period of Egyptian sculpture. A few paces to the south of the four colossal statues, is a recess hewn out of the rock with steps leading up to it from the river; its walls are covered with hieroglyphic inscriptions, representations of Isis, and the hawk-headed Osiris.

an edited excerpt from: Travels in Nubia by John Lewis Burckhardt, published in 1819

Clearing the fourty feet of accumulated sand above the entrance to the Ramesses temple was the work of several weeks and the cause of continual friction between Giovanni Belzoni and the local people who were far more interested in extracting the maximum amount of money from the Europeans than in the work of uncovering the temple. But Belzoni and the five men in his company determined to do the bulk of the digging themselves and suceeded in opening the temple. The below discription was written by two companions of Belzoni soon after the entrance was opened.

Travels in Egypt

and Nubia, Syria, and the Holy Land

by Charles Leonard Irby and James Mangles, 1823

Adapted for AscendingPassage.com, 2006

The Temple of Ramesses at Abu Simbel is situated on the West side of the Nile, between 200 and 300 yards from its' bank; it stands upon an elevation, and its base is considerably above the level of the river. It is excavated into the mountain, and its front presents a flat surface, the breadth of which is 117 feet.

In front of the temple are four sitting colossal figures cut out of the solid mountain, chairs and all, each 69 feet (21 meters) tall. They are, however, brought out so fully that the backs do not touch the wall, but are fully eight feet from it; and were it not for a narrow ridge of the rock which joins them to the surface from the back part of the necks downwards, they would be wholly detached. One of the statues has been broken off by a fracture of the mountain from the waist upwards.

There were originally twenty-two monkeys above the frieze and cornice, of these there are only twelve undamaged. Under the arm of one of the great figures we discovered the remains of the stucco with which they were once covered, and traces of red paint are discernible in many places. I think it very probable the whole front of the temple was once covered with stucco as the Egyptians have used that material very liberally and skilfully in the decoration of the interior. Of the cornice over the door, which was once perfect, there is not at present more than a foot in breadth remaining, just over the corner where we entered.

The four colossal figures in front of the temple are all of men; they are in a sitting posture, above sixty feet high, and the two which we have partly uncovered, are sculptured in the best style of Egyptian art, and are in a much higher state of preservation than any colossal statues remaining in Egypt. They are uncovered at present only as far as the chest. Before the recent excavations one of the faces alone was partly visible, as was part of the head gear of the other remaining two. The face of the statue, No. 2, whether taken in the front view or profile, is one of the most perfect specimens of beauty imaginable. It has so far resisted the effects of time, as not to have the least scratch or imperfection; and there is that placid serenity which one admires in most of the Egyptian countenances. The face of the statue, No. 3, has a more serious aspect; the nose is not so aquiline, nor is the mouth so well turned: it is not, however, without its beauties, and perhaps a connoisseur would say the features possess more character than the former.

Little space has been left between the figures on either side, and scarcely more in the center than sufficient for the door. The cornice above the door presents a very curious appearance; it has been broken by a fall of part of the rock above, and the chisel has since been evidently employed to form the remaining part into some other shape, or to fashion it for the reception of a new cornice, or for some other ornament.

The interior of the temple is 154 feet long by 52 broad (exclusive of the side chambers). It is comprised of fourteen separate rooms. The eight standing figures of Pharaoh Ramesses, 30 feet high, which ornament the outer hall, are as well proportioned as they are highly finished. The drapery of these statues reaches nearly half-way down to their knees, and is striped like that of the figures without. The features of the countenances are perfect, and they all have the hook and scourge (the usual emblems of Pharaoh) in their hands, which are crossed on the chest.

The interior of this temple is a work not inferior to any excavation in Egypt or Nubia, not even excepting the tombs of the kings at Thebes. Indeed, the effect produced on first entering it is more striking than any those can afford. The loftiness of the ceiling, the imposing height of the square pillars and of the erect colossal statues attached to them, and the dimensions of the apartments, which are on a much larger scale than any of the other excavations, all contribute to render the interior of this temple no less admirable than its splendid exterior.

The interior of this temple is a work not inferior to any excavation in Egypt or Nubia, not even excepting the tombs of the kings at Thebes. Indeed, the effect produced on first entering it is more striking than any those can afford. The loftiness of the ceiling, the imposing height of the square pillars and of the erect colossal statues attached to them, and the dimensions of the apartments, which are on a much larger scale than any of the other excavations, all contribute to render the interior of this temple no less admirable than its splendid exterior.The sculpture on the walls is not so well finished, nor is the coloring so perfect, as in the tombs of the kings; but the composition and invention of the designs, and their spirited execution, may be considered as equal to anything in Egypt.

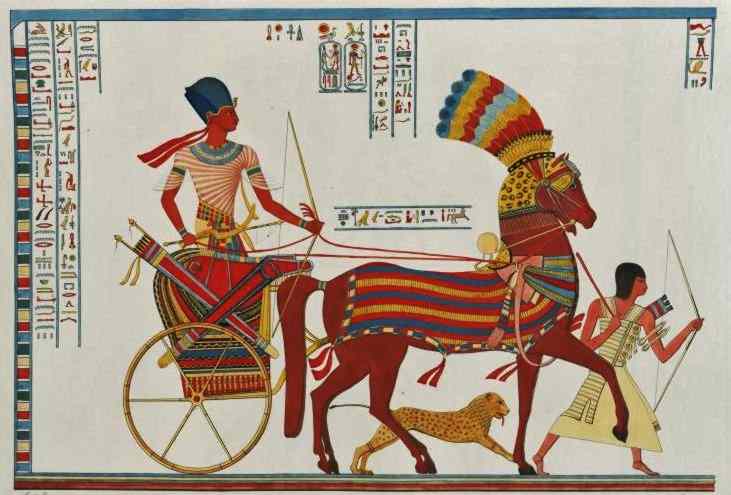

The extreme heat and closeness of the chambers, caused by the lack of free circulation of air, has injured the paint, but enough of the coloring still remains to enable the spectator to convince himself of the original beauty of the work. The most conspicuous groups represent the victories of Pharaoh Ramesses, the same as is depicted at Luxor, Karnac, and other parts of Egypt, together with triumphant processions and

consequent offerings to the deities.

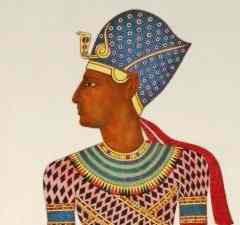

African portrats, Abu Simbel temple

from the Champollion expedition, published 1835-45.

The prisoners seem to be of different nations from those represented in other places. It is a circumstance of no little interest to see here, thus accurately painted, the costumes of the various tribes of the interior of Africa, at a date so remote that nowhere else can we expect to find any description either of their manners or their custom.

The most common dress consists of the leopard’s and tiger’s skin fastened round the waist, while the upper part of the body remains uncovered. The cap which they most commonly wear appears to consist of the leaves of the palmtree, dried and cut in slips. The workmanship is a sort of neat plaiting, apparently worked with much ingenuity. Those who wear the caps have no hair, others are distinguished by bushy hair and beards.

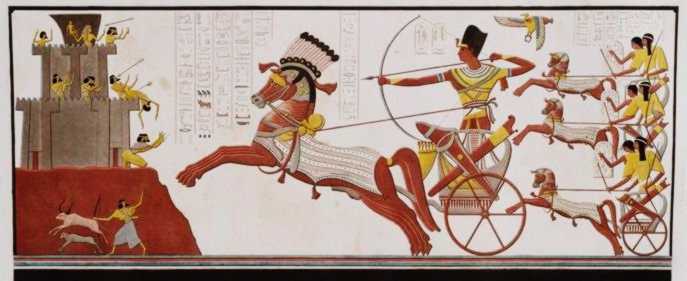

Art from Rameses II's Temple, Abu Simbel (Aboo Simble)

by François Chrétien Gau, 1819

In one of the groups is represented the storming of a fortress, of very singular construction. On the top are seen women, among whom one is in a sitting posture, wholly divested of drapery, and of a light complexion, bearing no resemblance in character or attitude to those represented in other places by the Egyptians. The hero who directs the assault is, as usual, of gigantic stature. On the plain below are seen the peasants driving their cattle away from the conqueror, designed with much spirited action; some of the besieged party are also kneeling and imploring clemency. The arrows are flying from all quarters amongst the defenders; and some are seen plucking them from their foreheads, arms, and other parts of their body.

In this temple we found several detached statues of calcareous stone. One of these, a little larger than life, is executed in a better style than is generally to be met with in Egyptian sculpture. The head and lower part of the legs are missing, as well as one of the arms, but the remaining parts sufficiently attest to the skill and good taste of the sculptor. The figure is an upright one, and seems to have represented Osiris, or Pharaoh Ramesses. The surface of what remains is scarcely injured; but the substance of the stone is so decayed by time, that any attempt to remove it would probably occasion its total destruction.

More art from Rameses II's Temple, Abu Simbel (Aboo Simble)

by Salvador Cherubini 1832 - 1844

A light black substance, which seemed to be decayed wood, was found in every apartment, in some places of the depth of 2 ft. Its substance, at the surface, was not unlike that of snow when it has been frozen over by one night’s frost. It cracked under the foot, leaving an impression. Many small pieces of wood were strewn about, apparently little injured by time, but which, on being touched, crumbled into dust. The wooden pivots on which the doors traversed still remain in the upper corner of all the entrances to the different chambers; and we also found fragments of wood in many places. Some of these appeared so perfect, that we thought of bringing them away, but they mouldered at the first touch. We were, therefore, very careful in leaving what remained for the benefit of future travelers. A broken brass socket, for the pivot of a door to traverse on, was also found.

The extreme heat of the temple was such, that Mr. Beechey spoiled his drawing-book while copying one of the groups, the perspiration having entirely soaked through it.

In the depths of the sanctuary is a bench with four sitting statues.

Edited excerpts from: Travels in Egypt and Nubia, Syria,

and the Holy Land by Charles Leonard Irby and James Mangles, 1823

The Sanctuary of Ramesses II,

two hundred feet deep in the rock,

is illuminated by the Sun twice a year.

Left to right: Ptah, Amun, Ramesses II, Re.

Abu Simbel Temple, by David Roberts, 1838

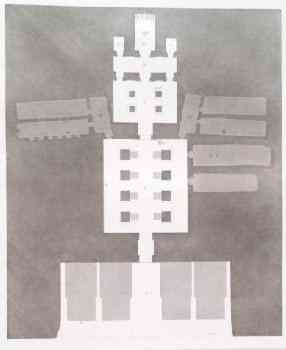

Floorplan of Rameses II's Temple, Abu Simbel (Aboo Simble)

by François Chrétien Gau, 1819

A small chapel of Thoth cut into the cliff on the left

and a free standing Sun chapel on the right

were still covered by sand and unknown to the artist.

No comments:

Post a Comment